Three years after his death, Bob Healey's estate is far from settled

Cool Moose founder's will, conflicts and claims bog down probate process

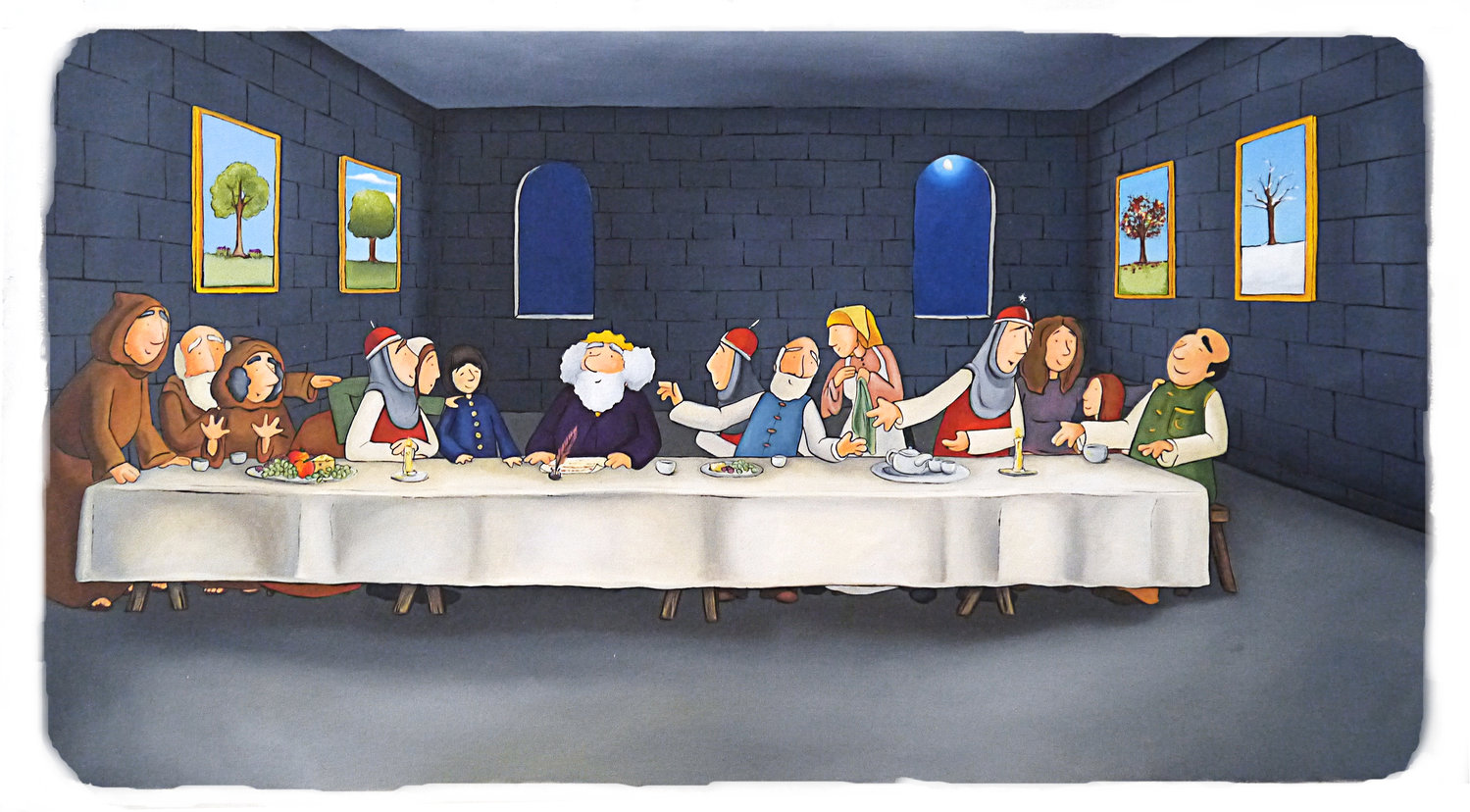

When Bob Healey was a young man, he wrote a children’s story about King Jovial, the happiest king in all the world. Like the man who created him, King Jovial had a long flowing beard and loved walking out into his kingdom, smiling along the way and greeting everyone he met — rich and poor, nobles and commoners — in friendship.

King Jovial was fascinated by the world. He loved hearing stories, listening to people of different standing, sharing a laugh and celebrating nothing more significant than a blue sky. And so he took these walks every day, year after year, and only concluded his daily visits when the sun set each evening. But one day, the sun refused to go down and the king, unable to go home, grew tired.

Three years after dying in his sleep at his Barrington home, as legal issues, hard feelings and questions cloud and delay the resolution of his complicated estate, the sun still hasn’t set on Mr. Healey’s legacy. And some of those who loved him are growing tired.

The Cool Moose

Over his many years as a central figure in the Rhode Island political scene, Mr. Healey, the founder of the Cool Moose Party, had become an icon here, not just for his looks — flowing beard, spectacles, ever-present black suit, white shirt, tie and sometimes, no shoes — but for his ideas.

The son of a Warren house painter and handkerchief factory worker, the Warren High School graduate worked as an attorney, concentrating on estate planning and probate law, zoning and other areas. He was known to do a great deal of pro bono work for causes or people he believed in.

Away from the legal realm, he was known more widely for his many campaigns for governor and lieutenant governor, an office which he held in contempt and pledged to abolish were he ever elected.

His slogans and handouts were unforgettable, and he often poked fun at himself with messages that cut to the bone: “Healey for Lt. Governor: He won’t be there for you” was one.

Mr. Healey was a popular figure but never won state office, and there were many in the political establishment who wrote him off and thought he could have gone further in politics had he just played the game and cut his hair. But that would never have happened, those who knew him say:

“Bob was just Bob,” Warren artist Jade Gotauco, his companion in his final years, said last week. “He couldn’t understand how he could be any different than he was.”

Knowing who he was, then, it surprised few in his circle to find his will, written about four months before his death, a confusing, complicated and amorphous work, though it may not have seemed it at first. Three years later, the will is no less confusing and his estate, no less settled.

A complex will

Mr. Healey, who had no immediate family, held assets totaling about $1.5 million at the time of his death and in his four-page will, spelled out where everything was to go.

He named his long-time friend and once-companion, Claire Boyes, the executrix of his will. She was to receive $1 million in cash, a life estate for his home on Sowams Road in Barrington, a percentage of any other assets not otherwise spoken for, and some land in Connecticut.

Ms. Gotauco, whom he knew for the last seven years of his life, was to get $30,000 in cash and a defeasible life estate allowing her to live in his Warren home forever, or until other heirs bought out her interest.

Others were bequeathed other assets and gifts, including long-time Providence Journal reporter Bob Mello, who was left $500 on the understanding that Bob would use it for “one great day at a racetrack.”

Natalia Machado-Lemos, another old friend from South America, was left $50,000 and land he owned in Uruguay. And others were to receive gifts, including an heirloom pump organ, cigars and wine.

Much of the will was classic Healey. He wanted to be stuffed and kept in a glass cabinet for one year following his death and upon that anniversary, be brought out and propped up for a “death anniversary party” for which he set aside $15,000. But stuffing a human is illegal under state law, and the party, which was open to “anyone willing to claim a friendship to me during my life,” never happened.

After the will’s particulars were examined and the estate entered into Barrington probate court under Judge Marvin Homonoff, the legal challenges — and a myriad of questions — began.

Creditors began coming forward, asking for the repayment of loans made, business investments returned, and the like. Those who claimed stake to some of Mr. Healey’s assets filed claims ranging from a few hundred dollars to many thousands. There were dozens, and they all got in line.

At the same time, attorneys started trying to weed through the will’s particulars, and found things that made them scratch their heads. Though Mr. Healey was versed in the writing of wills, he left few particular instructions on how to carry out his wishes. Who was to pay the mortgages and upkeep on his properties? Who had precedence in getting paid out? How was his debt structured? The more questions that were asked, the cloudier the issues became.

As Ralph Kinder, Ms. Gotauco’s attorney, puts it:

“It’s hard to say what his intent was. We don’t know. In my mind, it bears out the reason why you should not write your own will. Bob was a very capable attorney, but I wouldn’t have drafted my will that way.”

The Correias, the houses and the book

Though there are many roadblocks to the will’s resolution, the Correia Family Trust is one of the larger outstanding issues.

Prior to his death, Mr. Healey was trustee of the Correia Family Trust in Bristol, created when a resident of that town, Alice Correia, died in 2013. After Mr. Healey’s death, loved ones who had been left money in that trust came forward, claiming that Mr. Healey had withdrawn more than $130,000 of the trust’s funds into at least two separate accounts, and they needed to be repaid.

Warren attorney Tucker Wright knew Mr. Healey for many years. He considered him not just a colleague but a good friend, and said it has been a confusing process to navigate his old friend’s finances on the Correia Trust’s behalf.

While he does not believe Mr. Healey ever did anything with malice or criminal intent, the Correia trust funds are troubling, he said. He hired an accounting firm to get to the bottom of Mr. Healey’s withdrawals and, after learning from Judge Homonoff that a majority of the Correia case is a matter for Rhode Island Superior Court, not probate, brought the matter to the state court level. It remains there.

“I don’t think he ever intended to steal anything,” Mr. Wright said. “But he was very sloppy with his work, very sloppy.”

“He probably would say it wasn’t anything intentional. But you have to admit it is kind of like Bob. He was just so busy, and that was the problem. Bob wanted everyone to be happy. He was always going. I don’t think he thought it would come to this.”

The houses

While the Correias’ and other claims are being dealt with, other sticking points remain. Mr. Healey left few specific instructions in his will as to how the various upkeep, mortgage, utilities and other issues relating to his several local properties were to be dealt with. As a result, recent property appraisals of his homes — one at 75 Sowams Road in Barrington, the other at 665 Metacom Ave. in Warren — give a bleak picture of each’s condition. Both have needed roofing and other work for years, and with a lack of any of that work being done over the past three years, appraisers wrote in recent reports prepared on behalf of the estate that they are in danger of being written off as losses.

While there is little other contention at the Sowams residence, the future of the Metacom residence is up in the air and has been bogged by hard feelings.

Mr. Healey left the house to Ms. Gotauco, who had been living there for years prior to his death, in a defeasible life estate — meaning she could stay there indefinitely or until she was bought out by the Martinelli Family Trust, which he created in the will on behalf of some of his extended family.

Other members of that trust are seeking to buy out Ms. Gotauco’s share for the $35,000 payout he called for in the will. But according to Mr. Kinder, her attorney, things are not going well. Though some of it has to do with the normal squabbling that often accompanies estates that end up in probate, the issue has been compounded by the will’s requirement that there be 100 percent agreement among all the trust’s principals before any decision regarding the property is made.

“Supposedly (other trust members) do not have the money to buy her out, so they need to sell the place in order to get her out. But it’s hard to sell a piece of property with a teardown on it, and a tenant. So it could drag on.”

Ms. Gotauco knows she is in a tenuous position there, but she said she has made peace with the fact that she may have to leave one day.

“I’m OK with that,” she said.

The house still bears many traces of her former partner. His artwork is all over the walls, paintings and xeroxed collages remain, and she has many of his political mementos from over the years: Healey playing cards, old political signs and other memorabilia.

Ms. Gotauco knew Mr. Healey for the last seven years of his life, and said he was much more than the charismatic politician and omnipresent attorney most people saw. While he was an extraordinarily complicated man, he was an artist, a lover of life and a dreamer, she said. He loved to challenge people, loved to force people to take action to better themselves, and was irreverent — a maverick and a kid to the core.

In some ways, she said, that’s why she’s not necessarily surprised the estate has become such a hydra, with tentacles and vines heading in every direction:

“Maybe he did it to see what people were made of?” she said, smiling. “It would be just like Bob. He loved to challenge people.”

While she would be sad to leave the home and its many happy memories, much more important to her is honoring Bob Healey’s legacy, celebrating his life and honoring the things she believes were most important to him. Her main hope? That his book will one day see print.

‘The King Needs Sleep’

When he was in his mid- to late-twenties, Mr. Healey wrote “The King Needs Sleep,” a children’s story about a happy king with flowing hair whose idyllic, love-filled life was upset when the sun refused to go down one day.

Mr. Healey loved the book deeply, and though he always wanted to have it published, held off for years because he could not find the right artist, Ms. Gotauco said.

After they met at a friend’s Newport art gallery, Mr. Healey told her about the book, which ended after a young boy, Moon, was able to free the sun from its suspended perch in the sky.

Ms. Gotauco agreed to help him illustrate the book. They agreed on a deal for publishing rights — one that was agreed between them but never explicitly included in the will years later — and she spent the next several years illustrating the story. To date, the drawings from that project are perhaps her favorite collective works of art.

She believes the book should be published to honor his life and memory, but since publishing rights were never specifically included in Mr. Healey’s will, she has no rights to them. Instead, the text is a part of his personal possessions and as such, the ultimate say in what happens to the book lies with Ms. Boyes, his executrix.

Shortly after the will went to probate, and after getting what she said were discouraging responses to her request to have the book released for publishing, Ms. Gotauco filed a $30,000 claim against the estate for artistic services rendered.

Realistically, she said, the money is not what interests her, more important is the book itself.

“He loved it,” she said. “It would be a tragedy if it never got out.”

She still holds out hope, she said, but isn’t sure the book will ever see the light of day.

“It’s just a sad situation.”

What’s next?

Those involved say the legal issues clouding Mr. Healey’s estate are likely to take at least another year to navigate. And by the time they are all cleared up, Mr. Kinder predicted, claims filed by those whom Mr. Healey owed money to in life could eat into some of the funds that Mr. Healey set aside for bequests. He believes some of those left money in the will are going to walk away empty-handed, including Ms. Gotauco and others, like Mr. Mello, who were left smaller bequests.

Mr. Mello, a former Journal reporter, knew Mr. Healey for years and the two loved to talk and joke around whenever they bumped into each other.

“He knew I liked to go to the track and he always told me, ‘I’m going to leave you 500 bucks to go to a day at the races!’ ” Mr. Mello said.

When he heard following his friend’s death that Mr. Healey had followed through and left him the money, he had another good laugh. Now? He said he doesn’t ever expect to see a dime.

“I’m not holding my breath,” he said.

Gavin Hunter, too, doesn’t expect he’ll be paid the $13,000 or so owed to him by Mr. Healey after they resolved their liquor wholesaling business.

The former Barrington resident, now splitting his time between London and Bermuda, said the money doesn’t matter to him, and while he filed a claim to recoup it, “that’s just business.”

For months after the will entered probate, Mr. Hunter wrote letters to the court asking that the Healey case be brought back on track, and the many claims, some of which he didn’t believe had merit, be dealt with fairly.

“My biggest grievance here is that it feels as if the estate of Robert J. Healey is being raided unfairly,” he wrote in a letter to Judge Homonoff in June 2017.

“From the simple documentary evidence found in just two letters from Robert Healey, there would seem to be no justification for the repayment of loans that he clearly believed were repaid” years earlier.

“I have no vested interest in these matters except that Bob Healey was a dear friend and deserves to be treated better in his absence.”

Two years later, he said his concerns about his friend’s estate haven’t been assuaged:

“He was a kind man, he was a good man,” Mr. Hunter said. “I was owed money but I’ll never get it back with so many people with their hands in the till. But that doesn’t matter so much to me.”

“I think at the end of the day, everything that he wished for himself has been completely ignored. He wanted people to celebrate his life, but from the moment he was dead, these people have crawled over his assets in the most hideous way, really.”

What would his friend say if he could see what’s gone on the last three years?

“He would be angry,” he said. “He wouldn’t show it, but he’d be very disappointed and he would absolutely rewrite (his will). This isn’t what he wanted or wished for.”

“He was a peacemaker and he wanted everyone looked after.”