- SUNDAY, MAY 19, 2024

Yes, there is free lunch

The author describes how he discovered that the federal government’s free school food program is disproportionately benefiting the state’s wealthiest communities

I’m breaking protocol to tell this story in the first person, because the whole project really began at home in our kitchen. First, a little background. [If you want to skip my personal …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Please log in to continue |

Register to post eventsIf you'd like to post an event to our calendar, you can create a free account by clicking here. Note that free accounts do not have access to our subscriber-only content. |

Day pass subscribers

Are you a day pass subscriber who needs to log in? Click here to continue.

Yes, there is free lunch

The author describes how he discovered that the federal government’s free school food program is disproportionately benefiting the state’s wealthiest communities

I’m breaking protocol to tell this story in the first person, because the whole project really began at home in our kitchen. First, a little background. [If you want to skip my personal background and get to the discoveries, jump ahead to ‘So here’s what’s happening …’]

My wife and I live in Barrington with our five children/step-children. She has an extremely demanding job and is the first one out the door every weekday morning. Since Barrington shifted its start times a few years ago, sending the older kids to school later than any other school district in Rhode Island, she’s often out the door before any of the kids are even awake.

I stay behind to direct the crew (me included) through six breakfasts and six packed lunches in a chaotic burst of activity between 7:30 and 8:15 a.m. A couple of months ago, my stepson started ignoring his lunch. With the departure clock winding down, I’d ask what he wanted and he’d say, “I’ll just buy.”

Of course he’s not “buying” anything. I kind of knew school lunches were free; they had been ever since the pandemic began. But I didn’t really know how long that would last, or why it was happening, or who was paying for it.

To understand this story well, it helps to know how school lunch programs work today. Gone are the days of remembering (and trying not to lose) the milk money Mom or Dad gave you. These days every family has an account, the account is often tied to a parent’s bank account or debit card, and each child uses a code at checkout to record the meal in the family account.

If not watching the accounts regularly, parents can be unaware what their child is eating at school. A few years ago, when they were going to school in Rehoboth, my son racked up a $275 lunch bill without us knowing. Since we sent him to school with a packed lunch every day, we had no reason to check the account and didn’t know until we got an overdue notice in the mail.

Now that lunches are free, parents have no reason whatsoever to look at the meal accounts, and we receive no notifications about what the kids are or are not doing in the school cafeterias. The Barrington school district website actually includes no mention of the free meals program; the food page on the website reads like it’s still 2019.

Ok, so back to the kids. My next clue to what was really happening in the schools came when one of the boys ratted out the oldest son, revealing that he often goes to the cafeteria and gets a hot meal, such as cheeseburger and fries, even if he doesn’t like it, just so he can eat the fries.

We then learned that another boy brings his lunch every day, eats it and often gets another one for free. Then came my stepdaughter, who has lived most of her life with a severe gluten allergy. For health reasons, she has always gone to school with a lunch made at home. Yet last week, when I noticed she was running out the door with no lunch, I asked her about it and she said, “I’m going to buy; they actually have a lot of good gluten-free options now.”

That was eye-opening, but here’s the final straw. We learned just a few days ago that our youngest son “buys” breakfast at school every morning. I was stunned. He takes about 30 minutes to eat two bowls of cereal every morning, why is he eating a second breakfast at school???

The answer was simple — because his friend does.

I’m going to get to the real part of the story soon, but I feel like this behind-the-scenes narrative is relevant. My wife and I spend a lot of money on food; we can easily drop $300 on a Sunday trip to the grocery store, when we typically stock up for the week. We feed breakfast to every child every morning, and we have always packed a well-rounded lunch for every child every day.

Yet every one of the five kids has become a regular consumer of free food in the public schools, without us being aware, until recently, that it was even happening. Seems like we’re not alone …

So here’s what’s happening …

The personal discoveries above piqued my journalistic curiosity. First, who is actually paying for all these free meals? And by, “who,” I mean which set of taxpayers? Secondly, are children changing their behaviors?

The answer to the first question was easy to find. The U.S. Department of Agriculture funds school meal programs across the country, offering assistance for free and reduced lunches to school districts everywhere. Last April, the feds announced they would be providing funding to all states, for all children to eat for free in all participating schools and child care centers, for the entirety of the 2021-22 school year, all across America.

Here’s how it works. The students take food from the cafeterias (or in ‘stable pod’ situations, the food is brought to the classrooms). The vendor — private companies like Chartwells or Aramark — records what is “sold.” Those records get submitted to the district, which submits them to the Rhode Island Department of Education (RIDE), which then reimburses the districts for the cost of those meals.

So the child eats for free, the vendor gets paid and the federal government pays for almost all of it (RIDE contributes some from state coffers).

Back in December, I asked RIDE for records on the state’s lunch programs. I wanted to compare habits and costs two years ago, with habits and costs this year. I decided to ignore the 2020-21 school year because it was too abnormal. Many students spent all or half the year distance learning, so they weren’t going into buildings to eat school breakfasts or lunches. For purposes of comparison, those numbers would be useless.

Why are school lunches free to every student in America?

About a month after I asked, RIDE sent me piles of data. I received multiple spreadsheets and hundreds of pages of .pdfs. It took a while to sort through, build my own spreadsheets and make sense of it all, but a few discoveries were immediate.

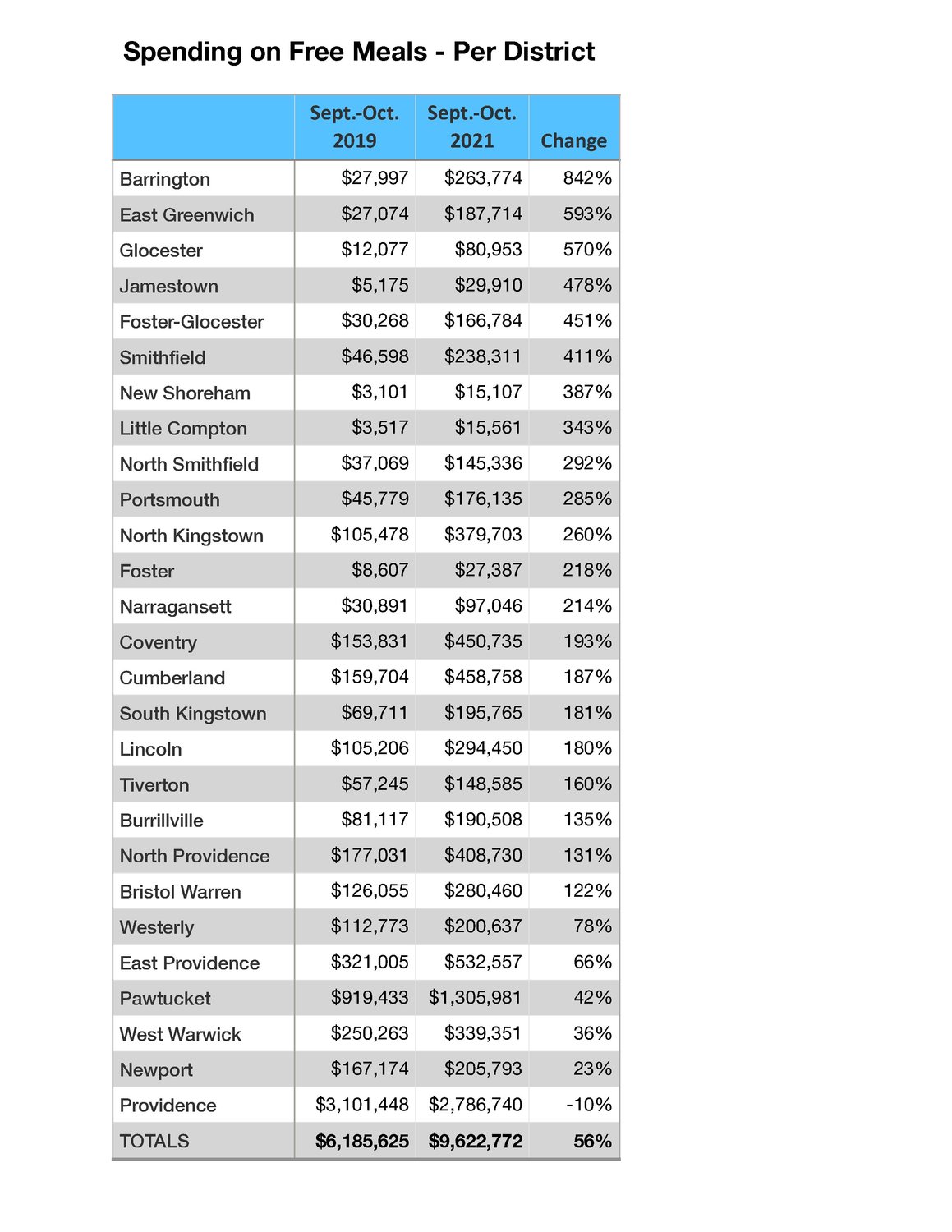

Yes, the subsidies for school food programs have increased dramatically. That’s obvious, since the federal government is paying for everything. Overall, it appears that spending on the breakfast and lunch programs has increased 56%. That’s based on an analysis of 27 public school districts, comparing food reimbursements in September and October of 2019, with food reimbursements in September and October of 2021.

During the 2019-20 school year — before Covid hit — RIDE was distributing $4 million to $5 million per month to the state’s school districts and charter schools. This school year, it is distributing some $6 million to $7 million per month.

The rich get richer

Another trend became surprisingly clear when I dug into the data. It seemed like the state’s wealthiest suburbs were benefitting the most from the free food program.

I looked at Barrington first, again studying differences between 2019 and 2021 in the first two months of the school year. I found a whopping 842% increase in federal payments to Barrington. Two years ago, the district received $27,997 from the state in September and October; this school year the district received $263,774. It was the highest increase in food subsidies in Rhode Island.

Next-highest was East Greenwich — a 593% increase, from $27,074 to $187,714.

It turns out all of the districts with the most significant increases in federal food payments are typically considered among the state’s wealthiest suburbs. After Barrington and East Greenwich in the list of top 10 beneficiaries are Foster-Glocester, Jamestown, Smithfield, Little Compton, North Smithfield, Portsmouth, North Kingstown and Narragansett, with federal spending more than tripling in all those districts (see chart).

The bottom six

Among the districts I was able to study (data was not complete for every district in the state), some of the most economically distressed communities saw the least impact from the new free lunch program. In fact, five of the bottom six are East Providence, Pawtucket, West Warwick and Newport, where federal reimbursements have increased between 23% and 66%.

And then there’s Providence, where federal spending has actually decreased 10%. The only explanation for that must be the socioeconomic and structural factors driving poor attendance, distance learning, close-contact quarantines and actual Covid infections and quarantines.

So while Barrington and East Greenwich are receiving five and eight times more money than they used to, the state’s most distressed urban district is receiving 10% less.

The new distribution in money is somewhat to be expected. Consider that many of the urban districts already had many of their students on free-or-reduced food programs before the pandemic hit. Thus, when the federal government made everything free, it had a less significant impact on the communities where many students were already getting the subsidies.

It makes sense that it would have the biggest impact on the wealthier communities, where far more students converted from paid lunches to free lunches.

But something else was nagging at me, and this goes back to my original journey into this story. Are the kids actually behaving differently? I kept digging into the data …

Some kids are taking a lot more

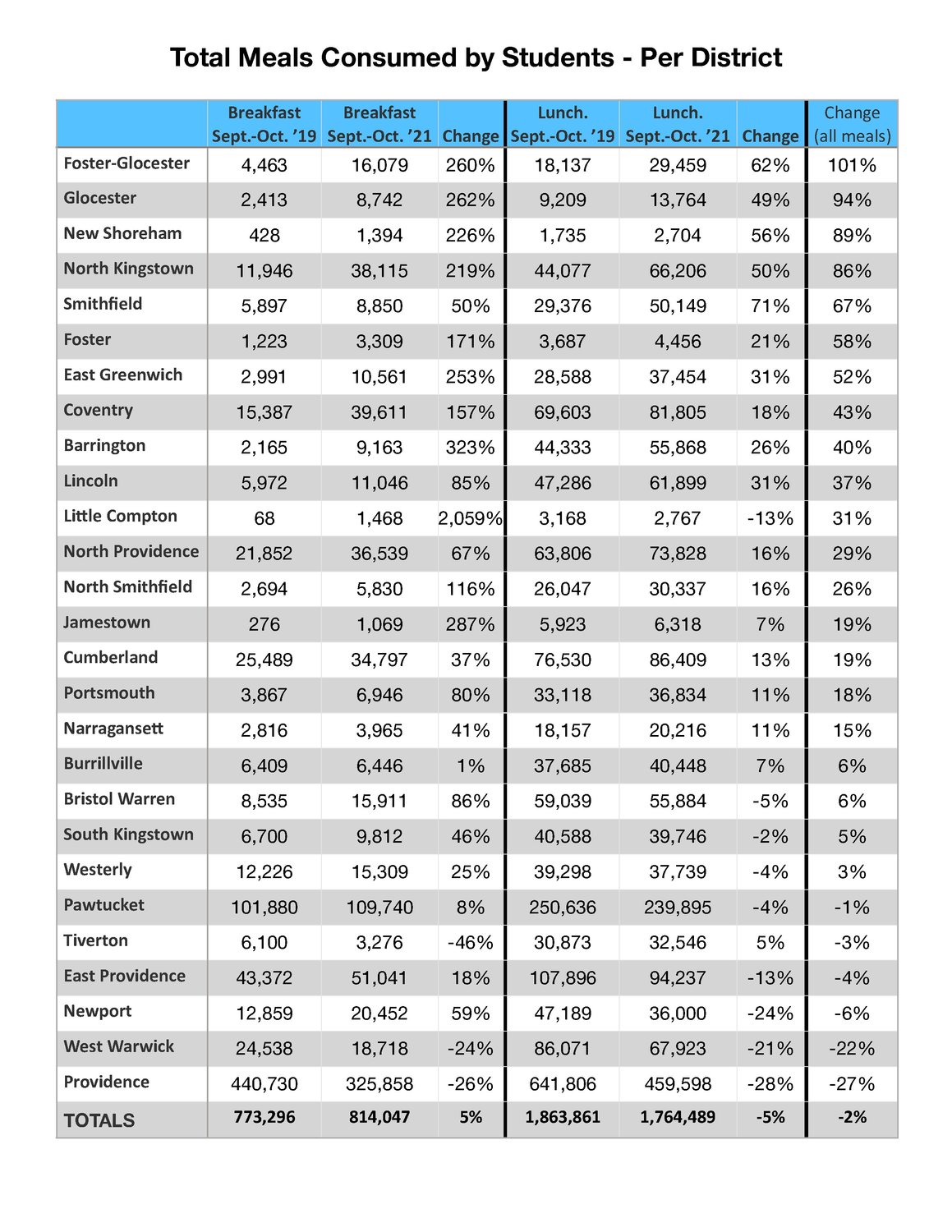

Take the time to pore through hundreds of reimbursement records and you make more discoveries. Some districts aren’t just getting a lot more money, they’re getting a lot more meals.

In Foster-Glocester, students are taking twice as many meals as they used to. Consumption of breakfast has nearly quadrupled, and lunches have almost doubled.

North Kingstown students are eating 86% more school meals than they used to.

This time Barrington is not the highest, but it’s in the top 10. Overall, Barrington students are taking 40% more meals, with breakfasts actually quadrupling (from 2,165 in the first two months of 2019, to 9,163 in the first two months of 2021).

Once again, the more distressed communities are near the bottom. School meals have actually decreased 27% in Providence; 22% in West Warwick; and 4% in East Providence. They’re basically the same in Pawtucket.

In many other places, like the Bristol Warren Regional School District, Tiverton and South Kingstown, habits have barely changed. The schools are serving nearly the same number of meals as they did two years ago.

In conclusion …

This is where the analysis pauses. I don’t know exactly why the changes in student habits are not universal. I don’t know why students in some communities are taking advantage of the free meal programs at far greater rates than students in other communities. I don’t know exactly why utilization has decreased in some of the most needy communities.

I have theories, but I haven’t done enough research yet to pose them.

For now, I’ll summarize what we’ve learned. The pandemic-induced federal school food program is pumping a lot more money into the state, with millions of dollars flowing to all the communities in Rhode Island. The meal programs are tracking to cost more than $60 million this year.

But the money may not be flowing exactly as the federal government intended, with the wealthier communities benefiting at far greater rates than the distressed urban communities.

The money also may be changing children’s behaviors in ways unintended. Enticed with free food, families are taking advantage more than ever before, with or without the parents’ knowledge. But it’s not happening the same everywhere. Some kids are taking a lot more free meals than their peers.

Other items that may interest you