Spreading the East Bay’s native history

A new marker placed on Child Street near Kickemuit Middle School strives to provide historical context on the Pokanoket settlement that long inhabited local land and explores King Philip’s War.

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Please log in to continue |

Register to post eventsIf you'd like to post an event to our calendar, you can create a free account by clicking here. Note that free accounts do not have access to our subscriber-only content. |

Day pass subscribers

Are you a day pass subscriber who needs to log in? Click here to continue.

Spreading the East Bay’s native history

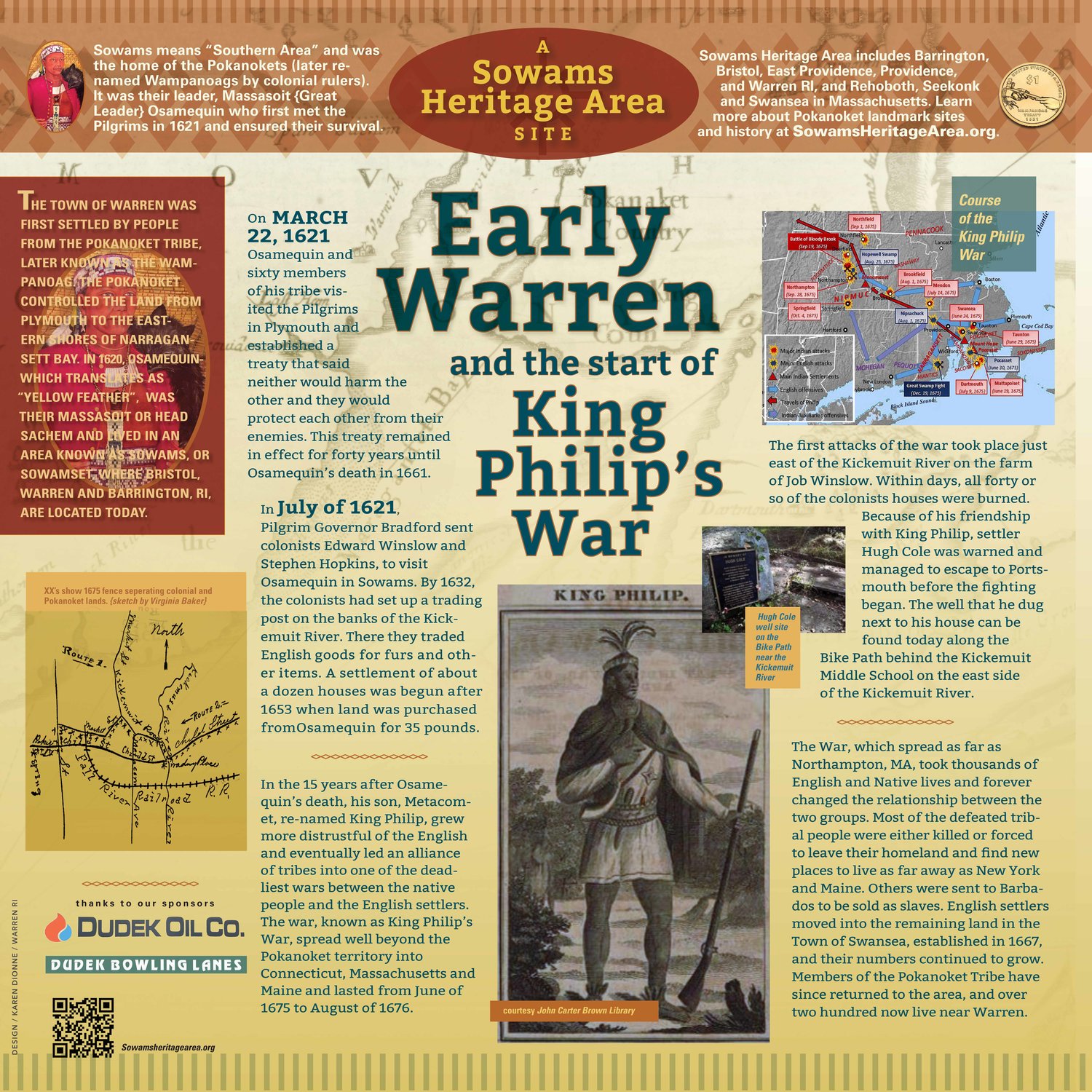

A new marker placed on Child Street near Kickemuit Middle School strives to provide historical context on the Pokanoket settlement that long inhabited local land and explores King Philip’s War, which fractured an unprecedented treaty between the indigenous peoples and early English settlers and set off a chain reaction of events leading to the disappearance (and eventual re-emergence) of the Pokanoket people.

The marker was installed thanks to funding support from a legislative grant to the Warren Preservation Society and through a donation from Dudek Oil Co. and Dudek Bowling Lanes.

“What happened here changed everything. Right here in this spot,” said Dr. David Weed, coordinator of the Sowams Heritage Area Project, to a group of KMS students assembled at the unveiling of the marker on Friday.

Dr. Weed told the students how the Pokanoket chief Osamequin called the land that now encompasses Warren home, and how his approach and interaction with early English settlers was instrumental in the survival of the colonists.

“In March of 1621 he walked the 42 miles to Plymouth…with 60 of his warriors and met with the Pilgrims there and struck an agreement with the Governor that the English would not harm them and they would not harm the English,” Dr. Weed said. “That treaty stood for his whole life, and guaranteed that the English would survive and eventually thrive in this area.”

“Were it not for that treaty, none of us would be here,” he underscored.

Dr. Weed went further into historical events that culminated from that treaty, which enabled the expansion of English settlements further into the surrounding areas, such as Swansea and what would become Barrington.

“[The English] got more and more successful and had children and wanted to provide land for them so they could farm,” he said. “All this area began to fill up with farms, including a farm right here on this property with Job Winslow.”

It was this Winslow farm property, upon which KMS is now located, that would become the site of the first major conflicts of the King Philip’s War — which resulted following the death of Osamequin and increasing tension between the Pokanokets and the colonists. King Philip, students learned, was not an English monarch, but the name chosen by Osamequin’s second son, who took over for his father as head chief of the tribe.

“People do not want to be invaded. They want their homeland back, and the Pokanoket people here wanted their land back, and it started disappearing,” Dr. Weed explained. “So they started by looting some of the farms around here. Eventually a 12-year-old shot one of [the colonists] and drew blood and that opened the war. Before you know it, houses were being burned in an attempt to get the English to leave and go back to England.”

Despite putting up a significant fight for more than a year, the Pokanoket tribe eventually ran short on munitions and food, and the English were able to prevail. Many natives were outright killed, while many more were forced to flee their ancestral homeland, or sold into slavery. They were forbidden from using their traditional Pokanoket title, and became forced to identify as part of the Wampanoag.

Descendants tell their story

Dr. Weed introduced Po Pummukoank Anogqs (which means Dancing Star), Sachem of the Pokanoket Tribe, to show that the Pokanoket people did ultimately survive and return to their native lands, which is known as Sowams. That land encompassed what is known today as Barrington, Bristol, Warren, East Providence, and Providence, RI, as well as Rehoboth, Swansea, and Seekonk, Mass.

“People have existed for well over 10,000 years before colonists came…We were the caretakers of this land and I want to pay respect to my ancestors who did just that. They took care of this land and everything on it and lived in peace and harmony and balance with everything in it,” she said. I would also like to pay respect to the Pokanoket people today who are still doing that so we can all benefit from the land and water of Sowams.”

“I just want you to know that the history of this land is so important, and where you live in so important in the history of what has happened here in America,” she continued. “And you should know that history.”

Pokanoket Sagamore Po Wauipi Neimpaug (meaning Winds of Thunder), the 10th generation great grandson of Osamequin, spoke next.

“You should be proud of your history, because this is where it all started,” he said. “It didn’t start down on the Cape.”

To learn more about the Sowams Heritage Area and the history of the Pokanoket Nation, go to SowamsHeritageArea.org.