She lived her dream, and learned how to fly

In “Fly Girl,” the most recent book by local author Ann Hood, she chronicles her eight years spent as a flight attendant for TWA (Trans World Airways). Escaping her “small, depressed mill town” of Warwick, R.I.” to see the world was her primary goal. She just knew that whatever exciting was happening, it was “far from West Warwick.”

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Please log in to continue |

Register to post eventsIf you'd like to post an event to our calendar, you can create a free account by clicking here. Note that free accounts do not have access to our subscriber-only content. |

Day pass subscribers

Are you a day pass subscriber who needs to log in? Click here to continue.

She lived her dream, and learned how to fly

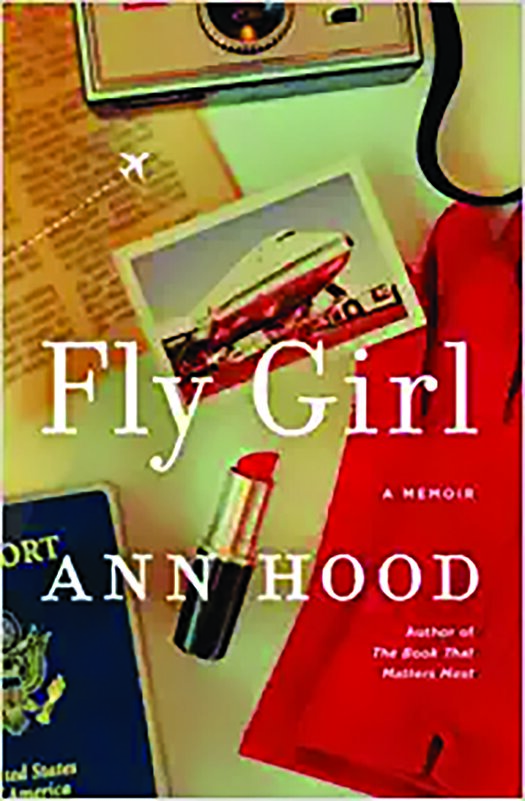

‘Fly Girl: A Memoir’

By Ann Hood

In “Fly Girl,” the most recent book by local author Ann Hood, she chronicles her eight years spent as a flight attendant for TWA (Trans World Airways). Escaping her “small, depressed mill town” of Warwick, R.I.” to see the world was her primary goal. She just knew that whatever exciting was happening, it was “far from West Warwick.”

Ann yearned to visit the pyramids, the Coliseum, The Eiffel Tower. After graduation from University of Rhode Island in 1974, she applied to various airlines hoping for what she considered a glamorous and exotic life. She had been a teen model for the Jordan Marsh Company at the Warwick Mall and felt her poise and wholesome, all-American look would be perfect for what she wanted to do since age eleven.

She was not deterred by the admonition from a high school teacher that “Smart girls don’t become airline stewardesses.” In addition to her consistent A+ grades, she had participated in extra-curricular activities and was the girl who always raised her hand. She found that the position she aspired to had many rules by which to abide: first, she must be single; under 115 pounds; not taller than 5’4”; younger than age 28; had to be “reasonable pretty around the hips, which was eye level for passengers”; had to be well-groomed, perfectly made-up; willing to conform; to relocate; and be a proficient swimmer.

Candidates hoping to pass the TWA requirements were dismissed for wearing the wrong lipstick or unsuitable shoes, for chipped nail polish, for looking sullen, chewing gum or smoking, and most often gaining weight. As a result, many developed extremely unhealthy eating habits: nine bananas one day, nine eggs the next, nine hotdogs the third, or just water until a pound or two was lost. Use of diuretics was common, in addition to sweating in a YMCA sauna. Some simply passed out from dehydration.

Hood set her sights on Pan Am. Accepted in 1979 as one of 550 out of 14,000 applicants, she began her training at Breech Academy in Kansas City. Although her college friends considered such work no more than that of a “glorified waitress,” Ann saw it as a great opportunity.

The instruction at Breech was demanding – classes in the theory of flight; memorizing aircraft routes and schedules; practice evacuating from the cockpit on a rope about 30 feet high; studying plane crashes, what caused them and how people were and weren’t saved; how to find and use fire extinguishers; how to inflate and launch a raft in turbulent seas. All of this for each of seven different types of aircraft brought her to tears.

In addition, she mastered how to mix proper cocktails, carve a chateaubriand, toss a salad while standing in the aisle; administer oxygen; deliver a baby; demonstrate safety equipment, as well as conduct an evacuation; practice troubleshooting broken coffee makers; set up liquor carts; balance meal trays; deflect angry, unruly, drunk passengers or romantic overtures; locate and operate emergency equipment, and practice water-ditching from a mock up plane into a swimming pool.

When Hood began her career, luxury travel was at its height. Frank Sinatra played a show in an American Airlines lounge; Continental had a Polynesian Pub offering a Cordon-Bleu chef; Maxim’s of Paris catered Pam Am’s first-class meals; United Airlines put orchids in the cabins and created volcanoes with crème de menthe and dry ice. The 747 had a spiral staircase on which the flight attendants practiced the proper way to walk in high heels — a sort of ankle crossing walk — as they repeatedly carried trays of food and cocktails to the upper level.

Ann found that her four years of college were a breeze compared to the four weeks of training at Breech. Once hired, she learned the newest recruits got the worst flights. Much time was spent on call, waiting for notice of an assignment; the phone rang constantly, sometimes at 3 a.m. with just an hour to get to the airport. It was all unpredictable and hectic; she would often run onto a plane without knowing its destination. Her pager was with her at all times, “ready to buzz, with a call summoning her to Vegas or Wichita.”

An attendant might have flown multiple flights in a single day, eaten only peanuts and coffee, feel exhausted and spent, having served a hundred or more passengers drinks and full meals in just over an hour; then again, and again and again only to disembark and see a supervisor waiting to check the length of her skirt, the dangle of her earrings, her lipstick, the way her scarf was tied.

One attendant was fired for not having her jacket on while walking through the airport. An executive said a TWA hostess should “always look as though she has stepped out of a bandbox and is a feast for the eyes.” As for the uniform, Ann loved its smart and chic look, simply relished cutting a sharp figure as she strode proudly through the airport.

She talks about meeting celebrities – Barbara Streisand, Ryan O’Neal, F. Lee Bailey, Liberace, Paul Anka, Wayne Newton, Glen Campbell, Ethel and Joan Kennedy, even Benji the dog in first class – as well as giving resuscitation to a dying man, breaking up love-making beneath a TWA blanket, an overdose in a lavatory, and comforting a passenger who had just learned of a younger sibling’s death.

She attributes much of her success and independence in her later life to being a flight attendant. Having flown thousands of miles, helped thousands of people, navigated foreign new cities on her own, solved problems and made decisions, the responsibilities incumbent in that job turned her into a confident, mature, sophisticated, worldly woman.

“Glorified waitress? Not at all. I had the best job in the world.”

She also believes that the conversations and experiences with travelers — the cadences of their dialogue, the way they reacted to things — provided insight into human nature, very valuable for her subsequent work as a writer.

Hood deplores the changes that have replaced the glorious hey-day of air travel – the well-dressed and fashionable passengers, the first-class amenities of fine wine and champagne chilled in silver ice buckets, linen napkins, exquisite meals – now replaced by endless rounds of pretzels, chips, or cookies. She blames deregulation in 1978 for the demise of seven major airlines that went bankrupt and later corporate greed in the 1980s. By that time her first novel, “Off the Coast of Maine,” had sold, and she was on her way to becoming a professional writer.

In conclusion, the book is an interesting coming-of-age evolution from a dreamy teenager intent on spreading her wings to a mature, self-assured, and capable woman. At the beginning, Hood’s detailed description of a plethora of different planes — the DC-9, the 727, the 727-200, the 707, the Lockheed 1011, the 747, etc. — seems to overwhelm the reader with more than one might want to know about aviation.

However, when Hood focuses on her personal experiences, arduous training, feelings of elation and success when she finally gets her wings, her satisfaction at her accomplishments as a representative of TWA, her delight in the exotic adventures the travel afforded her — it becomes more personal and alive.

There is some needless repetition — her fondness and near-ecstasy regarding her smart TWA uniform, for example, as well as the multiple skills required of a “flight attendant — never a “stewardess”! Not only does Hood convey her love of flying, she also succeeds in making it nearly palpable for her reader.

Donna Bruno is a prizewinning author and poet recently recognized with four awards by National League of American Pen Women.