- SATURDAY, JULY 27, 2024

Ground zero for 1938 Hurricane: More vulnerable than ever

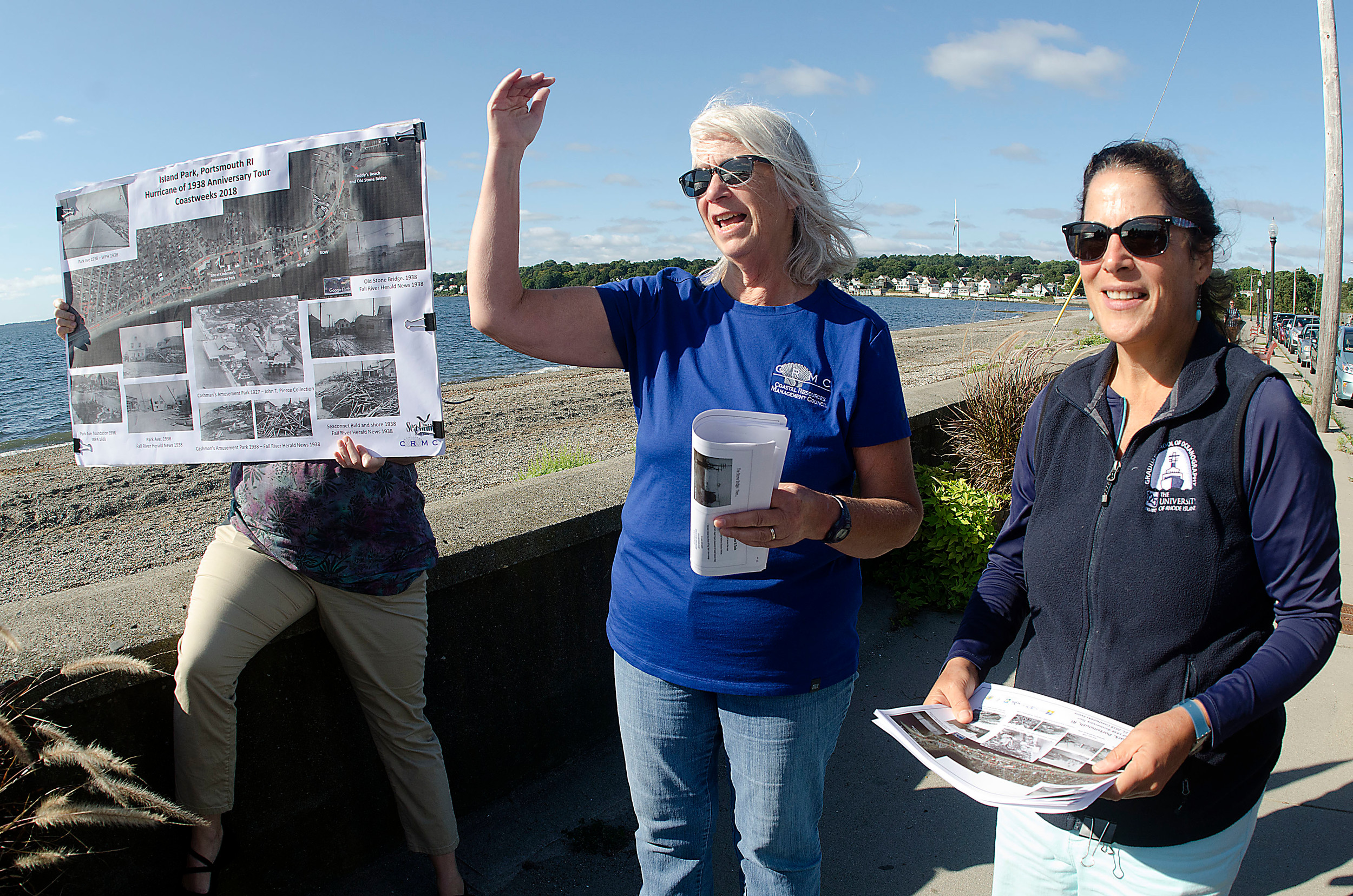

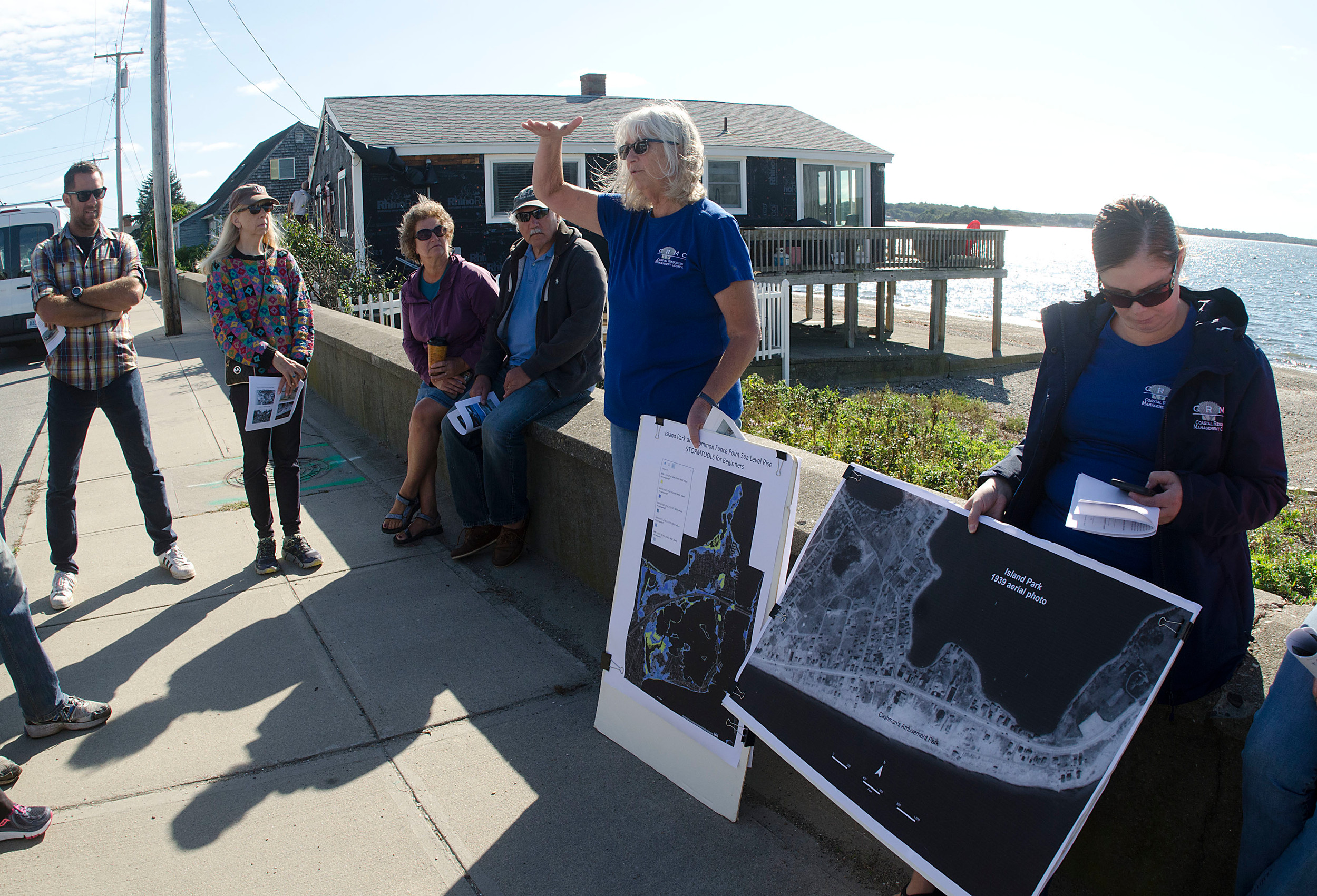

Experts plug coastal resiliency during walking tour of Portsmouth’s Island Park

PORTSMOUTH — On the 80th anniversary of the 1938 Hurricane’s devastating blow to Island Park and elsewhere, Town Historian Jim Garman talked about the past while coastal climate experts tied it to the present.

“The storm surge was a 12-foot wall of water that came up the river. Some of the homes here were pushed to the Montaup Country Club,” Mr. Garman said to about two dozen people gathered Friday morning across from Flo’s Drive-In on Park Avenue.

Janet Freedman, a coastal geologist with the R.I. Coastal Resources Management Council (CRMC), reminded them it would be worse today, since sea levels are about 10 inches higher than they were in 1938.

“That 12-foot wall of water is going to be 13 feet today,” she said. “We’re really concerned about areas that are going to be impacted by one foot or two feet of sea level rise.”

And that’s precisely why Ms. Freedman and Pam Rubinoff, coastal resilience extension specialist for the University of Rhode Island’s Coastal Resources Center (CRC) and Rhode Island Sea Grant, were in Island Park on Friday. They were leading a two-mile “Hurricane of ’38 Anniversary Coastal Walk” — part of Coastweeks 2018’s lecture series — in hopes of educating citizens on what can be done in the face of natural hazards to make the coastline more resilient.

Also present was Michael Asciola, an assistant in the town’s planning department, which has partnered with CRC for more local outreach efforts; and Jen West of the Narragansett Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve (NBNERR), located on Prudence Island.

The tour started across from Flo’s and proceeded east to Teddy’s Beach, with a stop along Fountain Street, Seaconnet Boulevard and a beach in between.

What happened here 80 years ago is not unlike what residents of the Carolinas experienced recently with Hurricane Florence, Ms. Rubinoff said.

“They never thought they would see that kind of devastation; it’s similar to 1938,” she said, noting the storm took this area by surprise and was a fast-moving beast — traveling 600 miles in 12 hours.

“It was so fast, it was like a train. They called it the Long Island Express,” she said.

Ms. Freedman has a personal connection to the storm. “My parents met in the ’38 Hurricane in Providence,” she said, describing how they both fled to the second floor of the Arcade building to avoid the rising waters. “My mom said that appliances were flying by.”

‘Hot spots’

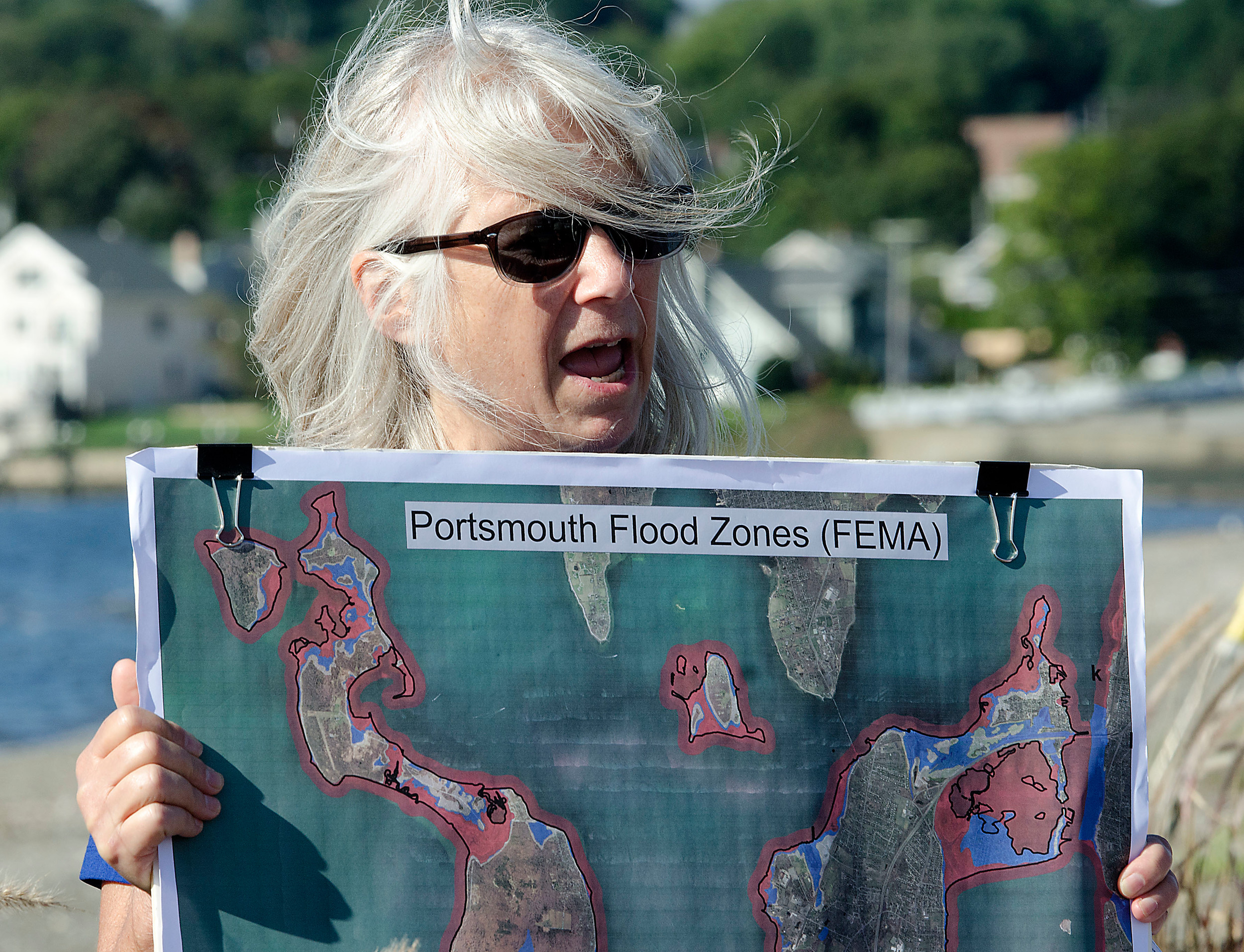

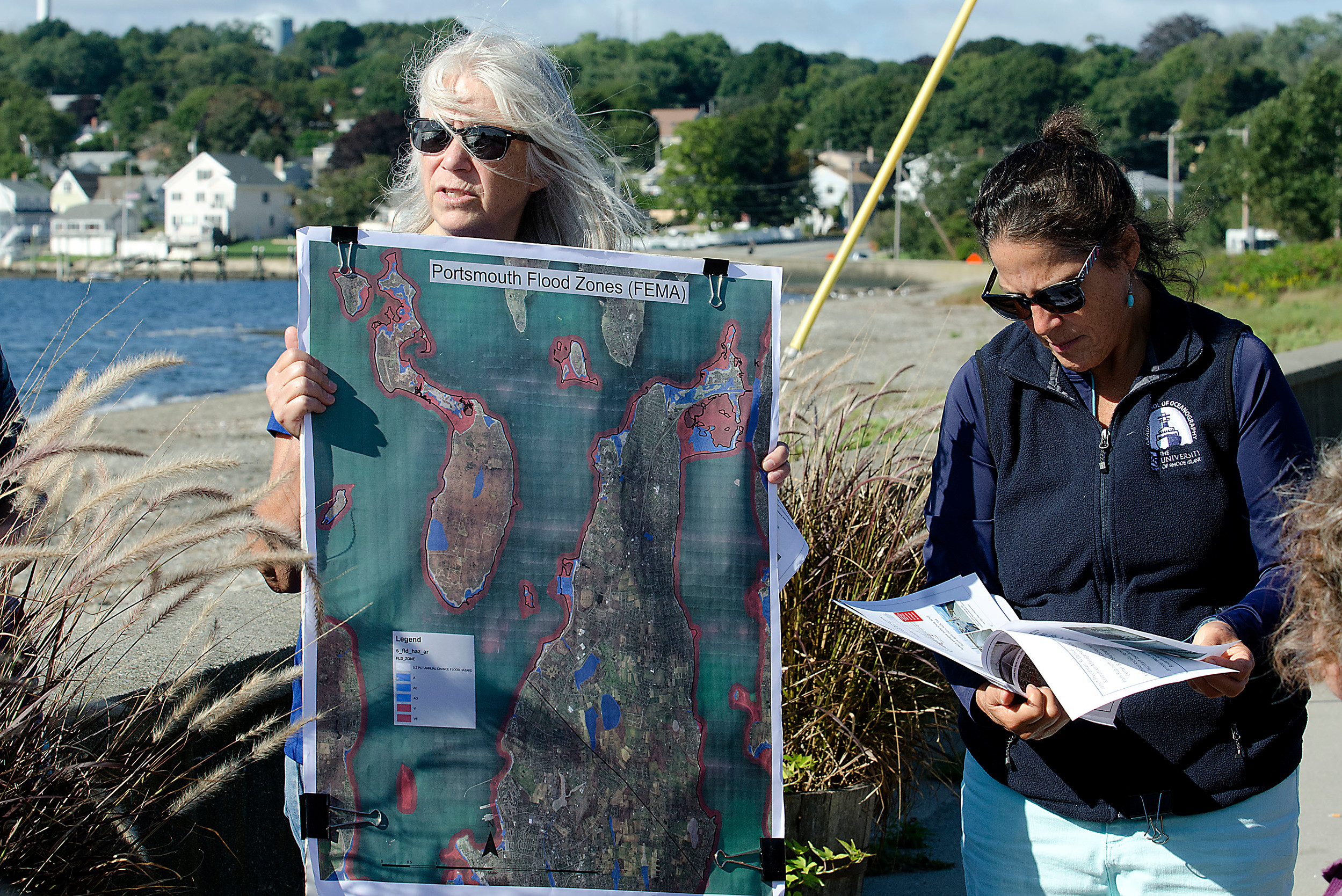

Portsmouth is a vulnerable area for coastal storms and flooding, especially Island Park, Common Fence Point and the Melville area, Ms. Rubinoff said. “In terms of flooding, they’re really the hot spots. But if you live up on East Main, you have to be careful with wind and power outages,” she said.

There are steps that can be taken, however, to lessen the impact of coastal flooding and sea level rise, they said.

Ms. Rubinoff and Ms. Freedman pointed to several houses along the tour that had been elevated, either by placing the foundation atop pilings or building the basement above ground. Under the Rhode Island building code, a home’s maximum height is 35 feet, plus up to four feet in freeboard in flood hazard areas, Ms. Freedman said.

By building up, she added, “federal flood insurance rates will go way down.” Federal rates vary, she said, depending on the location and type of construction.

A few of the houses also had exterior flood vents — they look like tiny windows — to allow water to flow in and out during flooding.

Of course, the simplest solution is to not build in a vulnerable, low-lying area. During a stop on Fountain Street, Ms. Rubinoff pointed to some empty beachfront lots with unobstructed views of the Sakonnet River and Gould Island — the result of owners not rebuilding after the 1938 Hurricane or moving their homes across the street, she said.

“Smart move,” added Ms. Freedman.

Citizen involvement

One of the goals of Friday’s event was to educate and empower citizens to get more involved in stemming the tide of sea level rise and its consequences, the presenters said.

According to Ms. Freedman, one foot of sea level rise translates to 60 more high tides annually. “That will flood your roads here. That’s something you have to think about in the future,” she said, suggesting the town build its roads higher in the future, or consider putting in causeways.

Sea level rise can also lead to septic system failures — particularly in low-lying areas such as Island Park and Common Fence Point — and contamination of local waters, she said.

Ms. Rubinoff pointed out that along Park Avenue, sea water is backing up into the storm drains during high tides and coastal flooding events. She asked local residents to keep an eye out for high water levels and to report them to state officials since Park Avenue is a state road.

“We encourage citizens like yourself to be educated and to ground our science,” she said.

Ms. Asciola urged residents to get involved with the town’s re-writing of its comprehensive community plan which determines the town's long-range goals and aspirations in terms of development. The next workshop will be held at 7 p.m. on Wednesday, Sept. 26, at Town Hall, he said.

“We’re at ground zero — one of the lowest areas in town and one of the most densely populated,” he said of Island Park and Common Fence Point.

Ms. West of NBNERR urged residents to view a series of six short videos (http://prep-ri.seagrant.gso.uri.edu) about coastal issues prepared by PREP-RI (Providing Resilience Education for Planning in Rhode Island), an online learning tool produced by CRC. PREP is now providing technical expertise to pilot programs, including one in Portsmouth, on coastal resilience initiatives.

Other items that may interest you