- FRIDAY, JULY 19, 2024

‘Rhode Island, I’d like an apology’

At ceremony honoring 1st Rhode Island Regiment, Ray Rickman says state must formally respond to its ugly track record on slavery — including possible reparations

PORTSMOUTH — With a likeness of “Black Regiment” soldier looking over his shoulder and several state lawmakers and other government leaders directly in front of him, Ray Rickman on …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Please log in to continue |

Register to post eventsIf you'd like to post an event to our calendar, you can create a free account by clicking here. Note that free accounts do not have access to our subscriber-only content. |

Day pass subscribers

Are you a day pass subscriber who needs to log in? Click here to continue.

‘Rhode Island, I’d like an apology’

At ceremony honoring 1st Rhode Island Regiment, Ray Rickman says state must formally respond to its ugly track record on slavery — including possible reparations

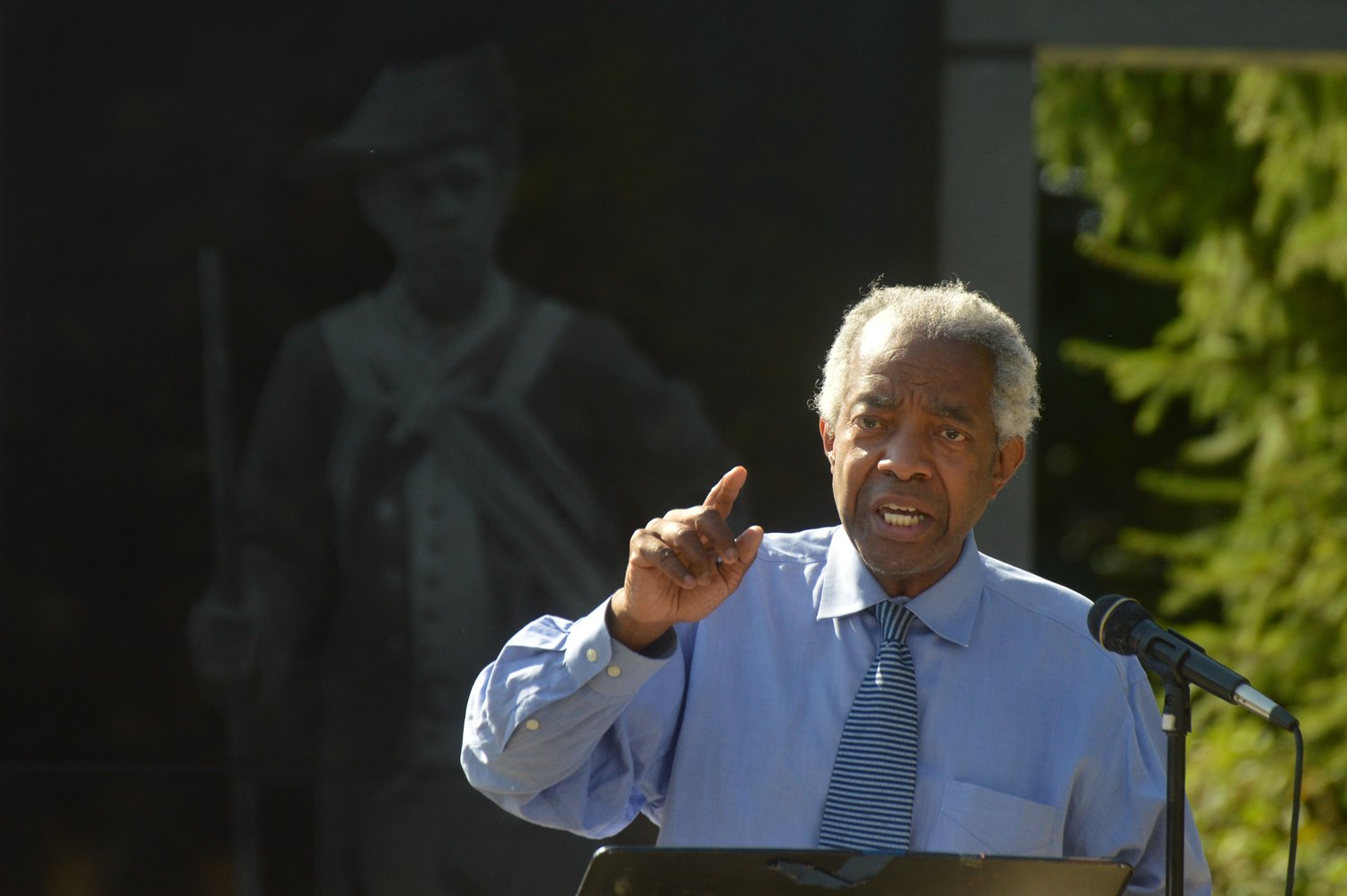

PORTSMOUTH — With a likeness of “Black Regiment” soldier looking over his shoulder and several state lawmakers and other government leaders directly in front of him, Ray Rickman on Sunday said it’s time for Rhode Island to formally come to terms with its culpability in the slave trade.

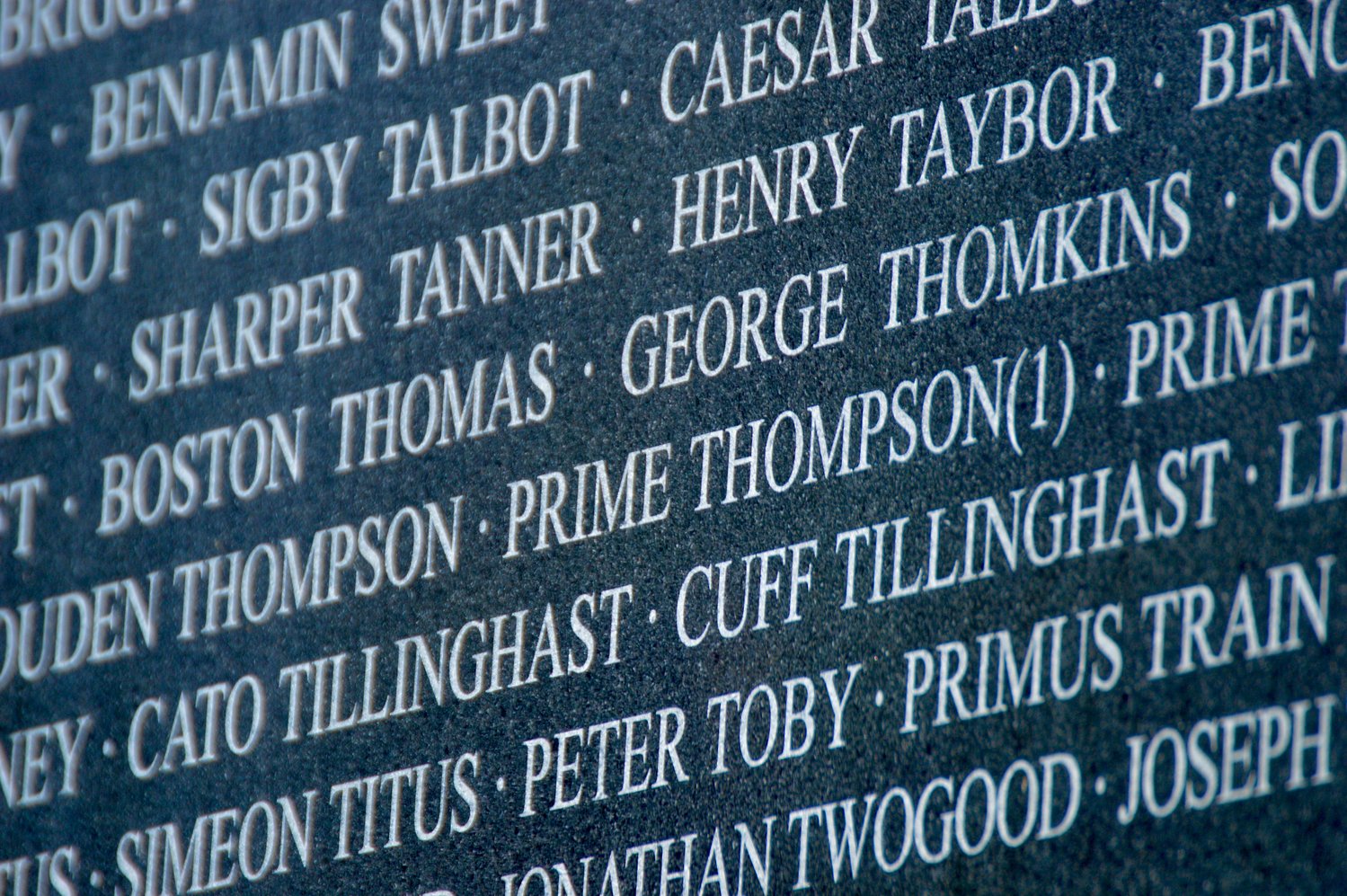

“Rhode Island, I’d like an apology,” Rickman said during the 55th annual ceremony commemorating the brave actions of the 1st Rhode Island Regiment — also known as the “Black Regiment” — during the Revolutionary War. The regiment was a contingent of slaves, freedmen and Native Americans who valiantly stopped the advances of the Hessian forces at the site of the park on Aug. 29, 1778 — 244 years ago — during the Battle of Rhode Island.

Rickman, a former state representative and deputy Secretary of State — the highest office held by an African-American in Rhode Island’s history — was the guest speaker at the event at Patriots Park, which was hosted by the Newport Country Branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Today Rickman is co-founder and executive director of Stages of Freedom, a nonprofit devoted to building bridges of understanding across the racial divide by celebrating Rhode Island African-American history in its black museum. The organization also raises money for Swim Empowerment, which teaches African-American youth how to swim.

Rickman didn’t mince words when speaking of the 1st Rhode Island Regiment, which fought with courage and honor for America’s freedom despite a less-than-honorable reason for its soldiers ending up in the Continental Army in the first place. The majority of the regiment was made up of slaves, he noted.

“One day you’re over in South County doing farming — drudgery, awful — or you’re cleaning up somebody’s house in Newport. And then off to the fog of war,” he said.

They were sent off to fight, Rickman said, because of a “bright idea” by Col. James Varnum to enlist slaves due to Rhode Island's struggles in recruiting enough white men to meet troop quotas. The state paid the slave owners for men, with half the money supposedly going back to the slaves, who were also promised freedom after the war. “But I’m suspicious,” Rickman noted.

Furthermore, he contended, the slaves took the place of their owners in doing battle.

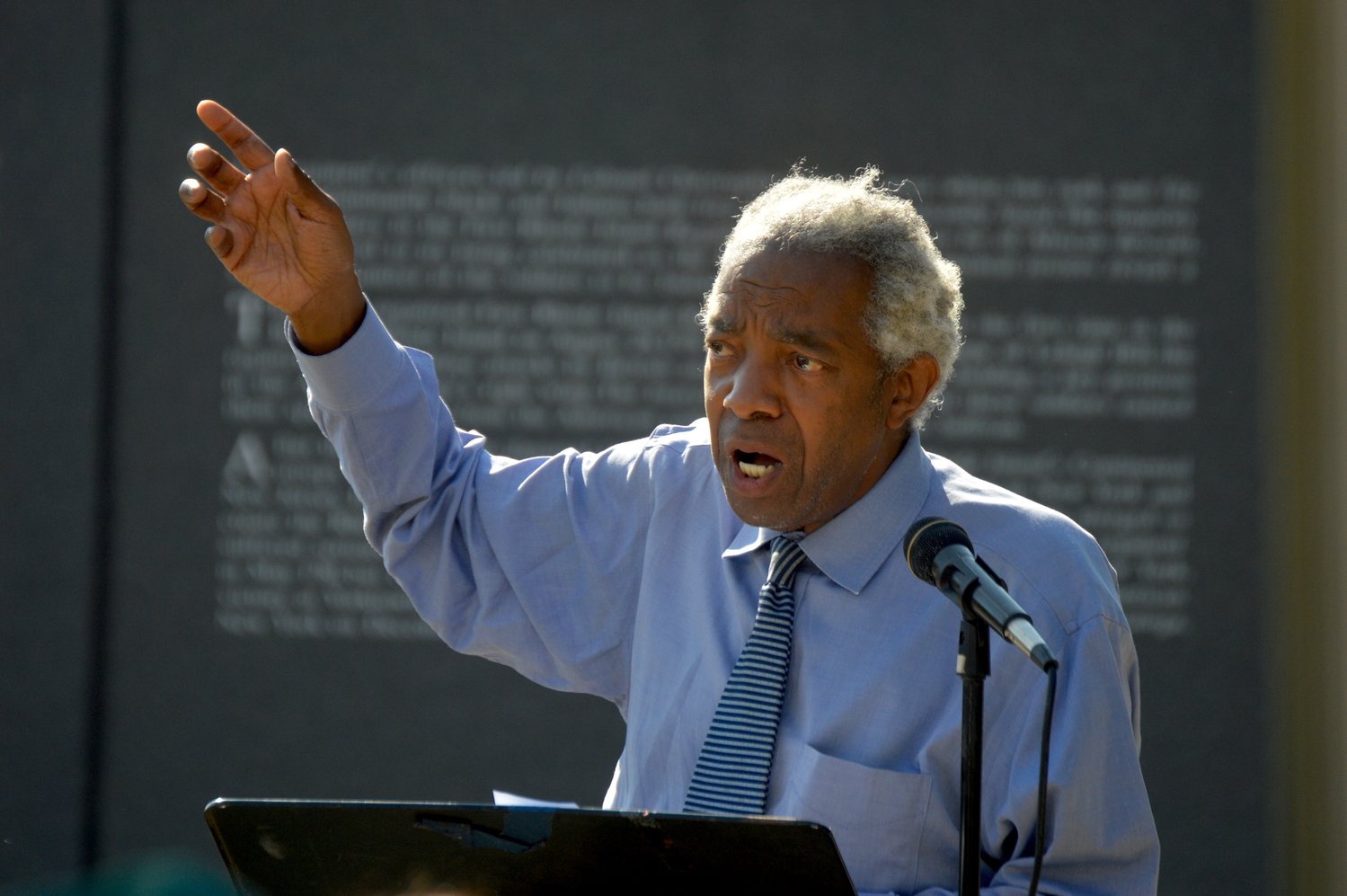

“The majority of them did not walk out of their house and say, ‘I want to sign up,’” Rickman said. “They’re sent by the slave owner. And he doesn’t send them because he loves the nation. The majority of them sent them to avoid military service. This is as disgusting a thing to be as a human being, to send a slave in your place because somebody might be killed, and you don’t want it to be you. And this is someone drug all the way from Africa in the bottom of a slave ship, and now off to Boston, so you don’t have to go. I want you to think about how disgusting that is, and how much honor they (members of the 1st Regiment) deserve.”

So the slaves went, but Gen. George Washington didn’t want them, he said.

“He’s a racist. He owns 212 slaves; he’s not a nice human being. This is the new Ray Rickman; the old one would have left that part out,” he said. In school, young students rarely hear about Washington being “a slave-owner of the worst order,” said Rickman, adding that our first president was even worse than Thomas Jefferson in that regard.

Washington had to “cave,” however, because little Rhode Island couldn’t otherwise come up with the needed number of troops, he said. At the end of the war, Washington admitted how effective the regiment was during battle, Rickman said.

Search is on

Stages of Freedom wants to identify 80 women or more as the descendants of the regiment members whose names are inscribed on the monument at Patriots Park, Rickman said, and then “ask the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) to accept them as full members.” That would bring “national attention to this group of men who helped make a nation,” he said.

DAR was the same group, he reminded the audience, that rejected singer Marian Anderson’s request to perform to an integrated audience in Constitution Hall in Washington, D.C. in 1939. In response, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt arranged for Anderson to sing on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial.

“Every other white person I know belongs to a racist organization, or recently did,” said Rickman, who had particularly strong words for Brown University, founded by slave traders Nicholas Brown and John Brown and other family members in 1764.

“It is disgusting, this history, and hidden from view,” Rickman said. “It’s only in the last 20 years that Rhode Island has been willing to talk about it. When you get up to talk about any of the slave-holders — the Browns and the like — and you’re at certain societies, they say ‘Will you be kind and not call them any names?’ And I say, ‘OK.’ Then I get up there and say, ‘John Brown was one of the worst human beings that God ever put on this planet.’”

Brown University has never apologized for its ties to the slave trade, Rickman said. “What’s happened in the last 20 years is that people, mainly white people, like to yell, ‘We’re all equal now!’ Now how can you be equal if the Browns have $300 million and not a single one of their slave descendants is wealthy as far as I know? They fly first class and most people of color fly no class,” he said.

Two years ago the state shortened its name — formerly The State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations — to remove language long criticized for its slavery connotations. It was a start, Rickman said, but not enough. “That’s one of a thousand things we should do,” Rickman said, noting that he has a more favorable opinion of reparations now than he did for many years.

“The City of Providence is doing reparations — $10 million, not much — and a formal apology. I’m waiting for the State of Rhode Island to do the same, because it was complicit,” he said. “An apology to the people of color formally from the state is in order. Germany has done it, and Germany gave reparations to Jews.”

The United States apologized and approved modest financial reparations to surviving Japanese-Americans who were incarcerated during World War II, he noted. “I’m not going to quantity who suffered the most, because to be picked out and destroyed in the Jewish case and to be incarcerated in the Japanese case is sickening for a nation to do that, and to do it to Black people for 300 years,” Rickman said.

A formal apology from the state to descendants of slaves, he said, would probably need to come from the General Assembly — several members of which were in attendance. “And that’s a small step, because I’m not big on apologies. I’m big on big flourishes,” Rickman said.

Others who participated

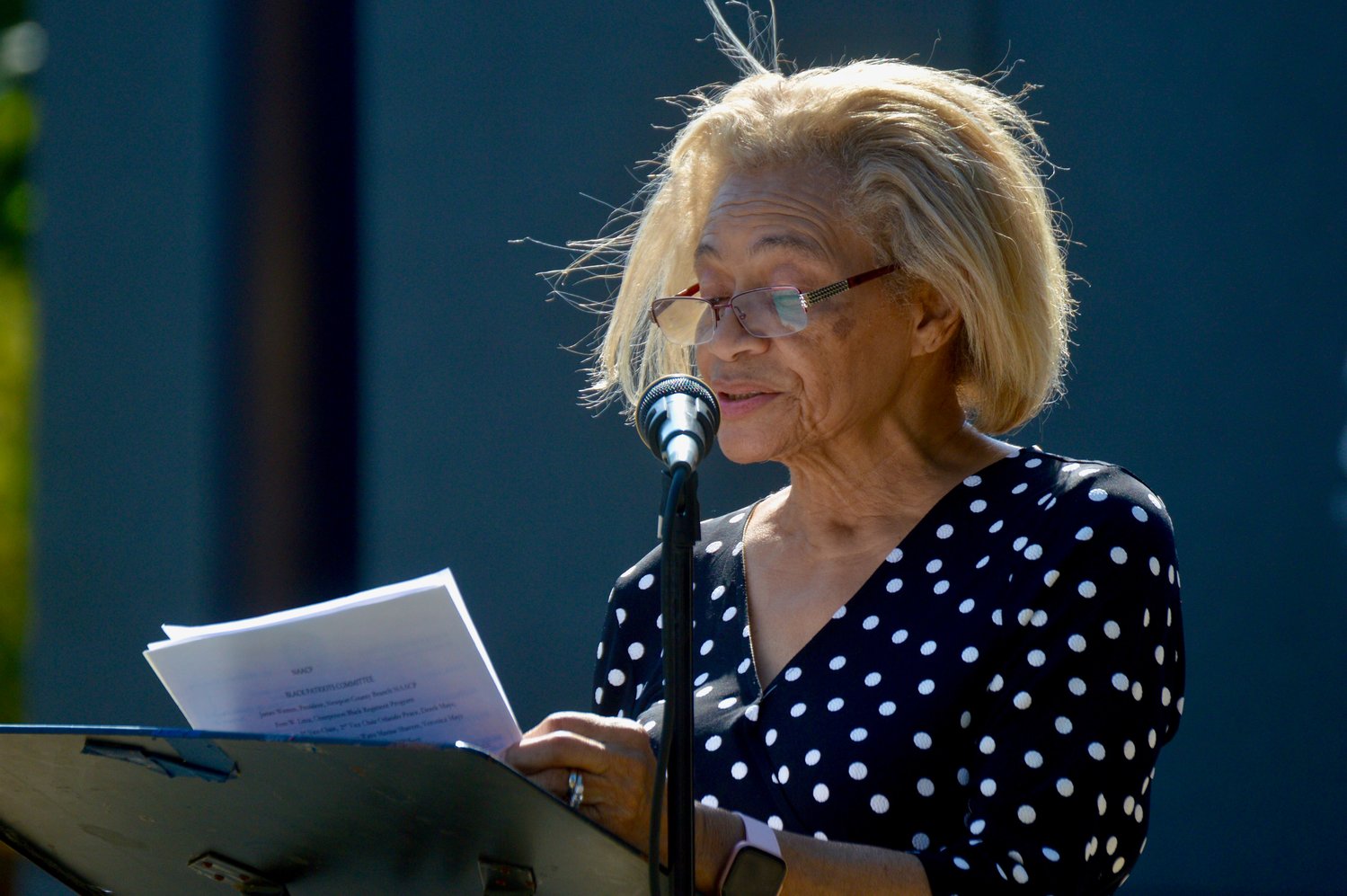

Alyse Antone Smyth, Rhode Island special assistant attorney general, served as mistress of ceremonies for the commemoration service. Also making remarks were the Rev. Dr. Cynthia Smothers of Newport, who gave the invocation and benediction; Jimmy Winters, president of NAACP’s Newport County branch; Frances Johnson, director of combined choirs at Community Baptist and Mr. Zion AME churches, who sang a solo and led everyone in the singing of “Life Ev’ry Voice and Sing,” also known as the Black National Anthem; and Fern Lima, treasurer of the local NAACP.

J. Clement “Bud” Cicilline, first vice president of the local NAACP, presented certificates of appreciation to two Portsmouth legislators who helped establish a Black Regiment Monument Commission to protect and maintain the monument, Sen. James Seveney and Rep. Michelle McGaw. (Note: Rep. McGaw is the author’s wife.)

Other items that may interest you